Plagiarism in Academia

In the last years, several public figures have lost their PhDs on grounds of plagiarism. Here, I want to find answers to the following questions. 1. Is plagiarism becoming more and more common? 2. How does the academic system contribute to fraudulent behavior? 3. Are specific people more prone to plagiarize than others?

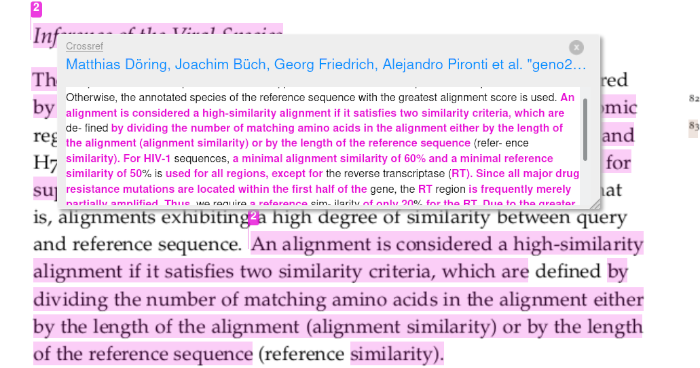

The Cambridge Dictionary defines plagiarism as ‘the process or practice of using another person’s ideas or work and pretending that it is your own’. In the last years, there have been several famous Germans who lost their PhD titles due to plagiarizing their doctoral theses. In Germany, VroniPlag is the largest open community that analyzes scientific work with respect to plagiarism. Most notably, in 2011, Guttenplag (a specific group of plagiarism hunters) published a detailed analysis of the doctoral thesis by Karl-Theodor zu Guttenberg, the German defense minister at that time.

In their analysis, they found evidence of plagiarism on 94.4% of the 475-pages long thesis. Initially, Mr Guttenberg declined all of the allegations stating that the claims were absurd. After more and more evidence came to light, however, he admitted his scientific misconduct. Finally, after an investigation by his alma mater, he was deprived of his title, and, due to the public outrage caused by his scientific misconduct, he also lost his ministry position.

Two other recent and well-known examples of plagiarism in Germany are the following:

- In 2013, Annette Schavan who was Federal Minister of Education and Research at that time, was denied her PhD title due to plagiarism. To defend her scientific misconduct, she unsuccessfully tried to argue that a thesis written in 1980 could not be evaluated using current academic standards.

- In 2019, Franziska Giffey, German Minister for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth was charged with plagiarism. After evaluating her doctoral thesis, the Free University of Berlin decided not to revoke her PhD since the deficits of the thesis were not found to be sufficiently serious for such a measure.

- In 2020, Shermin Voshmgir, a blockchain innovator, was found to have plagiarized large parts of her thesis. Despite obvious copy-pasting of whole sentences, she claims to merely have cited the content incorrectly. While this may be true for some parts, the existence of sentences that were completely copied from other authors suggests something else. Similarly to Annette Schavan, Ms Voshmgir also argued that her thesis, which was published in the early 2000s, should not be evaluated according to current scientific best practices. In this case, the controversial aspect is that the charges against here were put forward just as she had assumed a directorship for a blockchain institute in Vienna, which she lost in consequence.

There are two interesting points to notice from these examples:

- Deny first: It seems that individuals that are alleged of plagiarism usually immediately deny all of the allegations. They only admit to misconduct when they are forced to due to public pressure or insurmountable evidence.

- Evidence of plagiarism does not necessarily imply plagiarism: The question whether a piece of work should be considered as plagiarism is not a black-and-white decision but needs to be carefully evaluated. For example, an unwary person may produce a piece of work that has the appearance of plagiarism although it was never the person’s intention to defraud anyone (e.g. as for Ms Giffey). On the other hand, there are cases when the evidence strongly suggests that a work was deliberately plagiarized (e.g. as for Mr Guttenberg).

1. Is plagiarism becoming more common?

With the rise of prominent plagiarism cases in recent years, I would like to raise the question whether plagiarism is becoming more and more common?

I think that it’s reasonable to answer this question with No. To me it seems that nowadays it’s just more likely to be found guilty of plagiarism than in the past. This is largely due to advances in plagiarism detection software, which is able to compare a work to thousands of documents in a corpus within minutes.

Moreover, I assume that work published earlier than the 2000s is somehow more likely to contain evidence of plagiarism than recent work. One reason is that previously there was less sensitivity for this issue, particularly because potent plagiarism detection technology was not readily available.

Another contributing factor is that, with the rise of the internet, information about everyone, including their academic work is just fingertips away. Together with the appropriate tools, anyone can start an investigation.

2. Is there something wrong with the academic system?

The fact that plagiarism is such a big problem might lead one to think that there is something wrong with the academic system. Of course there will be some PhD students that lack training in proper scientific conduct. However, looking at a doctoral thesis where whole paragraphs are copied without any references, the main question to ask is the following:

Why didn’t the supervisor or any of the reviewers notice that the work was not the work of their student?

I think there are two answers to the question:

- Perfect deception: The work is plagiarized in such a way that it is not self-evident without computational analysis or (privileged) access to the original sources.

- Superficial reviews: Plagiarism is evident but the work was reviewed cursorily

I believe that in the first point is true in many cases: without computational analysis, even for an expert in the field, it can be very difficult to identify plagiarism. However, the second point also plays a role: if more time and effort were invested into reviews, some pieces of work would have never been published in the first place.

One problem of the academic system is that university professors may sometimes be too busy to perform diligent reviews on doctoral thesis, which are usually long (e.g. 200 pages or more) and hard to read. To prevent this problem, one possible solution to this problem would to increase academic funding, leading to more professorships. Another solution would be to create a legal limit on the number of PhD students that a single professor may supervise.

3. Is there an archetype for plagiarists?

There are observable trends among persons that have been identified as plagiarists:

- Persons where the PhD was not their primary goal but rather a means to an end.

- Persons that finished their PhD in record time.

- Charismatic persons with an aura of confidence.

The next paragraphs give an overview of the psychology of these groups and possible warning signs.

Case 1: Persons whose focus is somewhere else

People who are not focused on their thesis are more likely to plagiarize. They need to get the work done as quickly as possible due to their other responsibilities. So when they are pressed for time, they may begin to plagiarize.

It is no coincidence, that plagiarism is often identified in politicians (who often do a PhD alongside their political career) or physicians (who usually do their medical doctorates alongside their medical training or work).

Why do people in this category do not spend sufficient time on their doctorates? The likely explanation is that they see a doctoral degree as a career booster rather than having an inherent interest in academic research. So, if you see someone whose CV lists other time-consuming activities during his doctoral phase, (e.g. starting a company, working in a political party, doing consulting work) this may be a red flag.

Case 2: Persons that graduate quickly

People who finish their doctorates in record time (e.g. in only two years) may be extremely smart/time-efficient/driven or they may have taken a few shortcuts along the way, for example, when writing their thesis.

Therefore, if someone has completed his PhD very quickly, you may be right to wonder how that was possible and whether this is in agreement with that person’s actual competencies.

Case 3: Persons with an aura of confidence

Charismatic persons that ooze confidence and think highly of themselves are often assumed to be similarly competent. Due to the inherent assumption of competence, the work of such a person may be less diligently scrutinized than that of a more honest person. In this way, they may succeed in submitting sub-par work.

If you want to make sure that you’re not deceived by an impostor, always ask follow-up questions to identify whether someone really knows what they are talking about.

Are public figures more likely to be plagiarists?

Since public figures are somehow likely to exhibit some of the aforementioned characteristics (e.g. they are charismatic, driven, or may have used their degree as a stepping stone for their career), I think it is possible that there is a greater rate of plagiarism here. In any case, it is much more likely to be identified as a plagiarist if you are in the limelight. This is because inconsistencies in your CV or in your work will immediately attract public attention and further investigation. Moreover, as a public figure, there may be people who hold a grudge against you and who will try to bring you down.

Summary

Here, I would like to sum up my thoughts about plagiarism and provide some ideas ow how it could be prevented in the future.

Plagiarism is not becoming more prevalent

I don’t think that plagiarism is becoming more common. Rather, it’s just easier to identify plagiarism nowadays than at any other point in the past due to the existence of plagiarism detection software and the internet. To prevent the publication of plagiarized work, academics should check their work using plagiarism detection software prior to publication.

Doctoral supervision is lacking

Supervision and training during the doctoral phase is often insufficient. On the one hand, students should learn proper scientific practice. On the other hand, peer review processes should be thorough enough to prevent the publication of plagiarized work.

To improve the supervision of doctoral students, academic funding could be increased or the number of doctoral positions could be capped to a fixed number per supervisor.

Doctoral titles should not be a means to an end

In my opinion, there are too many people who strive for doctorates as a means to an end. Unfortunately, this is actually supported by some fields such as medicine. Here, doctoral studies are often undertaken merely due to the prestige of the title. Due to the short duration of the doctoral phase, which is often merely a year long, scientific output may lack in quality.

To ensure high-quality research, the same academic standards should be applied to all doctorates, independent of the field. Moreover, supervisors should make sure to vet potential candidates with respect to their academic aptitude and their personal integrity.

Comments

There aren't any comments yet. Be the first to comment!